By Stewart Lawrence

Strolling recently in Washington, DC’s, Rock Creek Park, I had a rare close encounter with one of the Park’s dwindling number of Great Blue Herons.

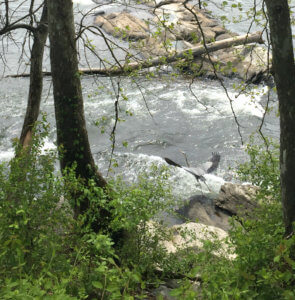

While joggers streaked by, oblivious to its presence, and rush-hour traffic passed noisily overhead, I sat in wordless wonder as the Great Blue, clinging to a half-submerged log, slowly surveyed its domain, then gently peered into the water with its fierce yellow eyes and double-billed javelin beak.

The Great Blue is less well known than its diminutive cousins, the White Heron and the Snowy Egret. It’s an enormous wading bird, standing roughly four feet tall with a wingspan nearly twice that length.

And yet it remains so still and blends so well into its surroundings that despite its outsized presence, it’s quite easy to miss. Once glimpsed, though, the memory of this statuesque, prehistoric-looking sentinel can prove indelible.

Herons are not alone in carrying a mysterious, even mystical aura. In some cultures, the nocturnal flight of an owl foreshadows death. Cranes, by contrast, are revered as symbols of longevity throughout Asia. And storks, as every American schoolchild knows, are harbingers of birth, frequently depicted in cartoons carrying newborn babies to their mothers.

The Great Blue? In flight, it looks something like a miniature version of the pterodactyl, a flying carnivore that once terrorized land animals and literally ruled the skies.

The Great Blue? In flight, it looks something like a miniature version of the pterodactyl, a flying carnivore that once terrorized land animals and literally ruled the skies.

But its sudden appearance, while often breath-taking, is no cause for alarm.

Native Americans have long viewed the Blue Heron as a powerful reminder of human strength and resilience. There’s a story told of an animal being chased by a wolf across a river. When the wolf arrives at the shore, it sees a Great Blue and demands the bird’s help in capturing its fleeing prey. Undeterred by the wolf’s menacing demeanor, the Great Blue offers to take the wolf across. But halfway there, the Heron announces to the wolf that its burden is too great. It tells the wolf to wait while the Heron goes back for help.

But the Heron never comes back. It just stands stolidly on the shore and watches the wolf drown. And the wolf’s prey? It scurries to freedom, delighted at its good fortune.

My first and most significant encounter with a Great Blue occurred twenty years ago when I was recovering from the collapse of my 11-year marriage. I was bereft, alone, and still in a state of profound grief. But I had just met a young woman, a fellow graduate student, and we’d become fast friends, then partners. Emotionally, we were two displaced people seeking more solid footing in our lives. And we were a looking for fresh inspiration, a sign perhaps that things would be okay, that we were okay.

One day in the Park, along the C&O Canal near Fletcher’s boat house, a Great Blue Heron suddenly appeared out of nowhere and flew just overhead. The way the bird seemed to eye us so closely in passing astonished and frightened us. Like startled children, we spontaneously cried out in unison. And the Heron, as if to reassure us, briefly slowed its flight to issue a resounding honk before continuing on its way.

The memory of that encounter still sends shivers of recognition down my spine. Angie is no longer with me but over the years I have grown in confidence, weathering life’s innumerable challenges and boldly spearing its joys. I have stared down those wolves that occasionally seem intent on devouring me whole.

Others sense that strength within me, too. Now and then, they look to me for calm reassurance and protection during their own times of loss and seeming peril.

And there I stand.

About the Author: Stewart Lawrence stumbled across the family encyclopedia at age six and has been writing passionately about his discoveries ever since. As a trained academic with a degree from Columbia University, he’s conducted field investigations in difficult-to-reach communities the world over. As a freelance journalist, he’s reported on the nuances of government policies, wars, election campaigns, and civic protest. His opinion columns have appeared in The Los Angeles Times, Christian Science Monitor, Huffington Post, and Politico. In his fiction and memoirs, he seeks to bring the same spirit of unflinching exploration to the mysteries of the human soul, as in his two literary essays, “Tutu’s Fluke” (2015), and “The Sour Taste of Mustard” (2016).